Publication date: 06/08/2022

Author’s note: Product teams at Meta rely on research along with other external factors to design and build products. This article discusses research conducted by Meta's Research Team to better understand people’s privacy needs. The author would like to thank her colleagues for their contributions to this project and related research: Product Designer Patrick Dugan, Content Designer Bryan Rinkus, and Product Manager Marcus Thomas.

Abstract

We wanted to explore whether lightweight educational prompts can help people feel more confident in their ability to control their privacy (“privacy efficacy”).

We conducted a survey experiment in which participants were exposed to education about the privacy settings available on Messenger or education unrelated to privacy.

Participants exposed to privacy education about Messenger felt more confident in their ability to control their privacy on Messenger and also felt more confident in the effectiveness of Messenger’s privacy controls.

Report

Can apps help people feel more confident about their privacy by providing reminders of the privacy controls that they offer?

At Messenger, we’ve found that people’s confidence in their ability to control their privacy (“privacy efficacy”) may be related to whether they use privacy controls when they have a need to do so (Menon, 2021). Therefore, we believe it’s important to explore strategies that might help boost people’s sense of privacy efficacy in order to equip them to handle their privacy needs.

Education is a key strategy that has been effective at boosting efficacy in contexts outside of privacy (e.g. Yehle & Plake, 2010; Amin et. al, 2018). This type of education can range from lightweight interventions that essentially increase awareness to more in-depth learning experiences. As a starting point, we wanted to explore whether lightweight educational interventions that remind people about Messenger’s privacy controls could be powerful enough to boost their privacy efficacy.

We can think of privacy efficacy as having two components: The first is self-efficacy, which refers to feeling confident that you can perform a task successfully, and the second is response-efficacy, which refers to feeling confident that doing a behavior will actually result in the outcome you want (Bandura, 1982; Floyd et al., 2000). We wanted to explore whether educational information about privacy controls could impact either or both of these components.

To test this idea, we invited a group of Messenger users to complete a survey in the Messenger app. In the survey, we randomly assigned each respondent to view one of three different mock experiences about Messenger’s settings. The mock experiences were designed specifically for this survey, and each mock experience contained a series of three static screenshots (images below). Two of the three groups viewed education about Messenger’s privacy features. For the first group, we designed the educational prompt to look like a settings menu. For the second group, we designed the educational prompt to look more like a guided “checkup” experience. The third and final group was a control condition. Participants in this third group saw an educational prompt about a Messenger setting unrelated to privacy (“Dark Mode”: A setting to change the Messenger app’s aesthetic from white to black). This control condition is useful because it lets us determine whether exposure to education specifically about privacy settings boosts privacy efficacy relative to exposure to any type of educational experience at all. After respondents reviewed the screenshots they were assigned, we then measured their privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy.

Figure 1. The privacy education prompt shown to respondents in the “settings design” group.

Figure Caption. The first screen shows information about Messenger's privacy settings and features. Tapping on 'Learn More' brings you to the second screen. Tapping on 'What others can see' on the second screen shows how you can control 'what others can see' about you on Messenger. Participants saw these screens as static screenshots with a description of how the screens related to each other.

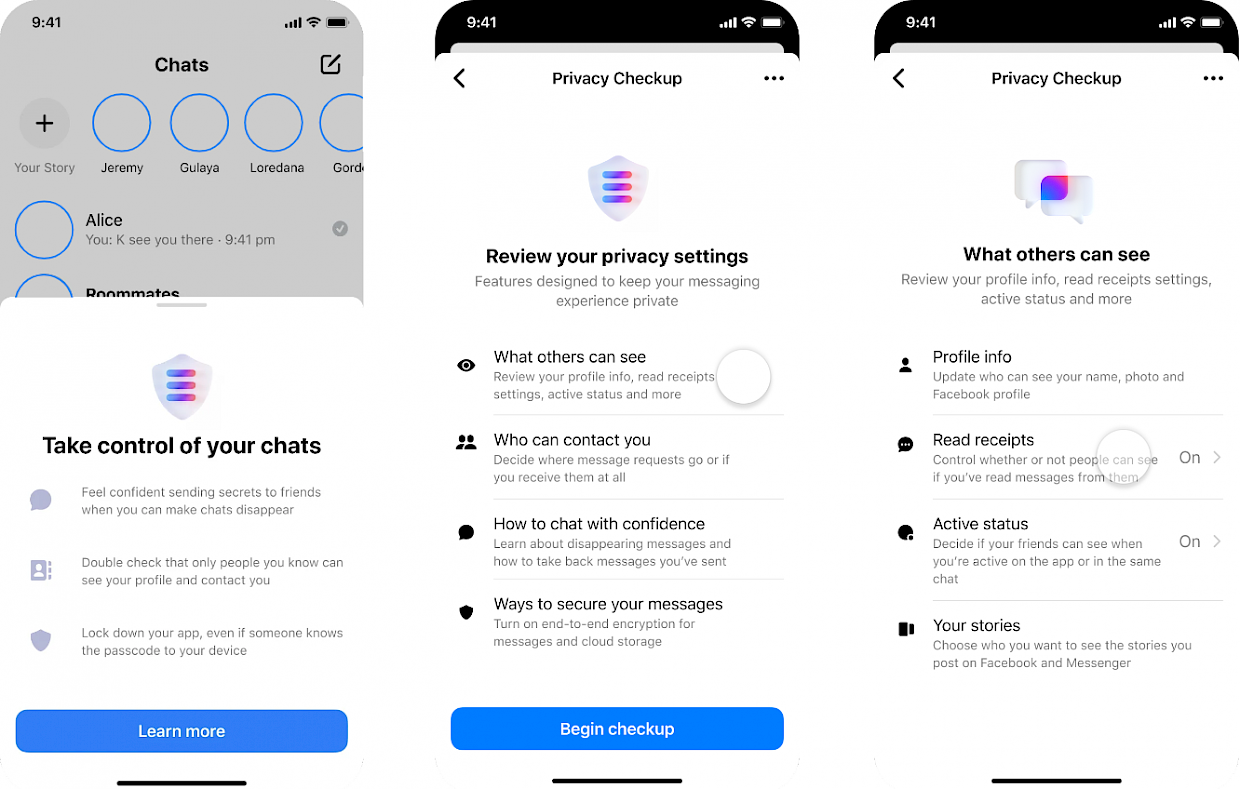

Figure 2. The privacy education prompt shown to respondents in the “checkup design” group.

Figure Caption. The first screen shows information about Messenger's privacy settings and features. Tapping on 'Learn More' brings you to the second screen. Tapping on 'Begin Checkup' takes you to the third screen, where you can control 'what others can see' about you on Messenger. Participants saw these screens as static screenshots with a description of how the screens related to each other.

Figure 3. The education prompt shown to respondents in the “control” group.

Figure Caption. The first screen shows information about Dark Mode, a Messenger setting that is unrelated to privacy. Tapping on 'Try it' brings you to the second screen. Tapping 'On' for Dark Mode changes the app's background color to black and takes you to the third screen. Participants saw these screens as static screenshots with a description of how the screens related to each other.

After viewing one of the three educational prompts, respondents were asked questions about their privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy on Messenger. Our hypothesis was that participants who were exposed to either version of privacy education would have higher privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy relative to participants who were exposed to education unrelated to privacy. However, we didn’t have a prediction about whether the settings design or checkup design would be more effective at boosting privacy efficacy — that was an exploratory question. For additional methods details including information about the survey sample and exact wording of survey questions, see the Appendix below.

In line with our hypothesis, participants who saw either of the privacy education prompts reported statistically significant higher levels of privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy for Messenger relative to participants who saw the education prompt that was unrelated to privacy settings.

Figure 4. Participants’ privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy were higher after viewing education about Messenger’s privacy features relative to viewing education about features unrelated to privacy.

Figure Caption. Privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy were statistically significantly higher for the settings and checkup education prompts relative to the control prompt that showed education unrelated to privacy. However, the differences in privacy self-efficacy and response-efficacy within the settings and checkup conditions were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

Providing users with information about the privacy controls offered in Messenger increased their confidence in both their ability to use those features and in the effectiveness of Messenger’s settings. This is evidence that lightweight educational interventions have the potential to improve users’ confidence in their ability to control their privacy on an app. At Messenger, we’ve begun providing this type of education within the Messenger app itself and also through supplementary sources, such as our privacy website that showcases a list of privacy controls available within Messenger along with video tutorials on how to use them.

Open Questions

Are boosts to privacy efficacy that result from educational prompts short-term or long-term changes? Because we measured privacy efficacy immediately after participants were exposed to the educational information, we can’t determine whether the effects persist or fade with time.

Another open question is whether privacy education has a dose-response relationship with privacy efficacy, such that more education consistently leads to more privacy efficacy. Although exposure to multiple educational prompts may continue to boost privacy efficacy, it could also be that there’s an upper limit on how much education can boost privacy efficacy. Understanding this relationship along with questions about short-term or long-term effects could help apps determine how often they should send privacy educational prompts to users.

The educational prompts we tested were lightweight because our goal was to learn whether even small educational interventions could be meaningful for users. Another natural question is whether more in-depth forms of education may have similar or even greater impacts on privacy efficacy.

Finally, the educational prompts in our research were delivered as part of a survey, rather than as part of the typical user experience of the Messenger app. It’s possible that the survey context may have impacted how respondents processed and interpreted the educational information. One way to explore that possibility would be to conduct a test with interactive, in-app educational privacy experiences.

Answering these open questions requires additional research. We hope to inspire other organizations to pursue some of these possibilities given how promising privacy education may be for improving users’ confidence in their ability to control their privacy outcomes.